Black Mountain College18.03.2022

From its conception and launch in 1933, to its closure in 1957, Black Mountain College was home to maverick thinkers and risk takers — a pedagogical place of inspiration for some of the 20th century’s most progressive artists and creators. The college’s name is born from its site’s original, rural coordinates in southern Appalachia, a small town miles shy of Asheville, North Carolina, called Black Mountain. Musicologist and liberal educator, John Andrew Rice Jr., established the BMC as an experimental teaching community, founded on rebellion and experiential practice. Its original class of 21 students, and celebrated pool of teachers, operated on the principle that to learn is to live through practice.

THE BEGINNING

From 1920 onwards, John Andrew Rice Jr. was revered by most he taught. “His Socratic style and ability to provoke free-ranging conversations drew students to his courses in increasing numbers.”1 Nevertheless, his oppositional politics and philosophies frequently disturbed and challenged the traditional practices of the American education system. By 1933, Rice would be fired from Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, after rejecting policies enacted by Rollins president Hamilton Holt.2 His departure inspired the resignation of additional faculty members, many of whom joined him in his venture to Appalachia to help build the community that became BMC.

At the time of the school’s founding, Europe’s society faced incredible social peril with the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime. The closure of Germany’s Bauhaus school and mounting persecution of people in Europe provoked a generation of artists and intellectuals to seek refuge in America.

In 1933, Rice invited artists Josef and Anni Albers, who were both former Bauhaus legacies and German exiles, to teach at the general arts college. As a former founder of the Bauhaus School and despite his humble knowledge of English, Albers was appointed the responsibility to establish BMC’s art department. Together, Josef and Anni Albers instilled the BMC with the spirit of the Bauhaus, carrying the heritage of the beloved modernist institution to America.

Only when I came back to Antwerp, which was five years ago, after a 10-year stint in Paris, did I pick it up again. Because I didn’t find a way to make Antwerp work for me. I just tried to transpose my Parisian life on a new backdrop, but that didn’t work. So I thought, “Okay, what makes Antwerp better than Paris?” and that was the low cost of studios. So I thought, “Okay, I’m just going to get some canvases, some tubes of oil paint, and see what happens.” And it’s really opened up this new chapter of my life in the city.

“Albers re-established what was called the Grundkurs, the foundation course, from the Bauhaus at Black Mountain. That meant for the art students a basis in materials and the belief in creativity through experiment.” — Steven Henry Madoff

According to Josef Albers’s former student, Frederick A. Horowitz, “Albers was at the center of things at Black Mountain College … His were the courses you took, whether or not you intended to continue studying art.” Although BMC was not defined as a fine arts school, the practice of making, experiencing, and experimenting — which were core tools for learning at BMC — are fundamental to the practice of fine arts; the subject matter heavily influenced the school’s curriculum.

THE ANOMALY OF BMC

Renouncing convention and status quo, Rice expressed harsh criticism towards common education rituals, namely approaches to teaching and learning through “lecture, over-reliance on ‘great books,’ memorization and counting credits by time in seat.” The founders of BMC believed that the “study and practice of art were indispensable aspects of a student’s general liberal arts education.”

At its core, BMC maintained five principles: the centrality of artistic experience to support learning in any discipline; the value of experiential learning; the practice of democratic governance shared among faculty and students; the contribution of social and cultural endeavours outside the classroom; the absence of oversight from outside trustees.

“Black Mountain College was fundamentally different from other colleges and universities of the time. It was owned and operated by the faculty and was committed to democratic governance and to the idea that the arts are central to the experience of learning.” — Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center

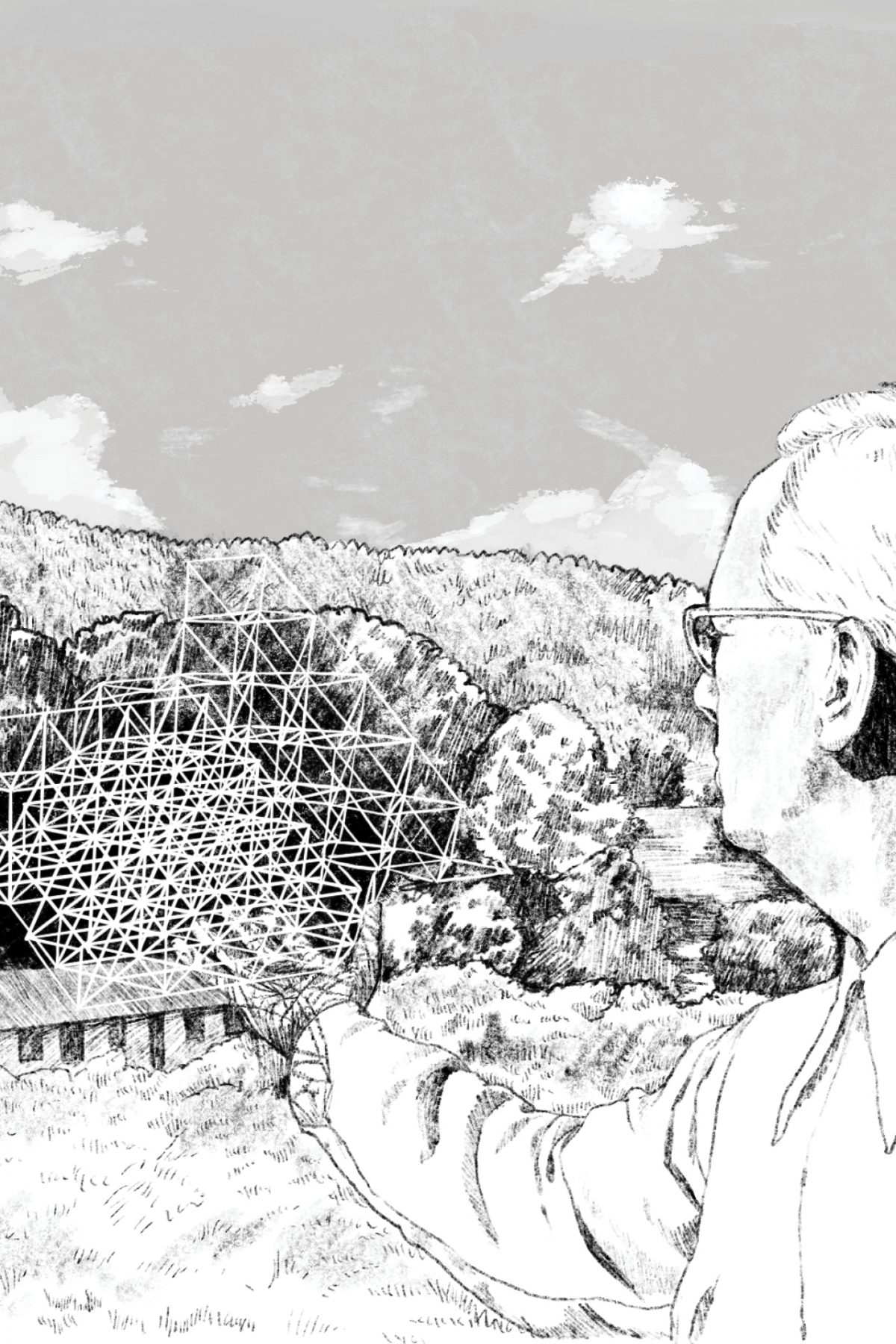

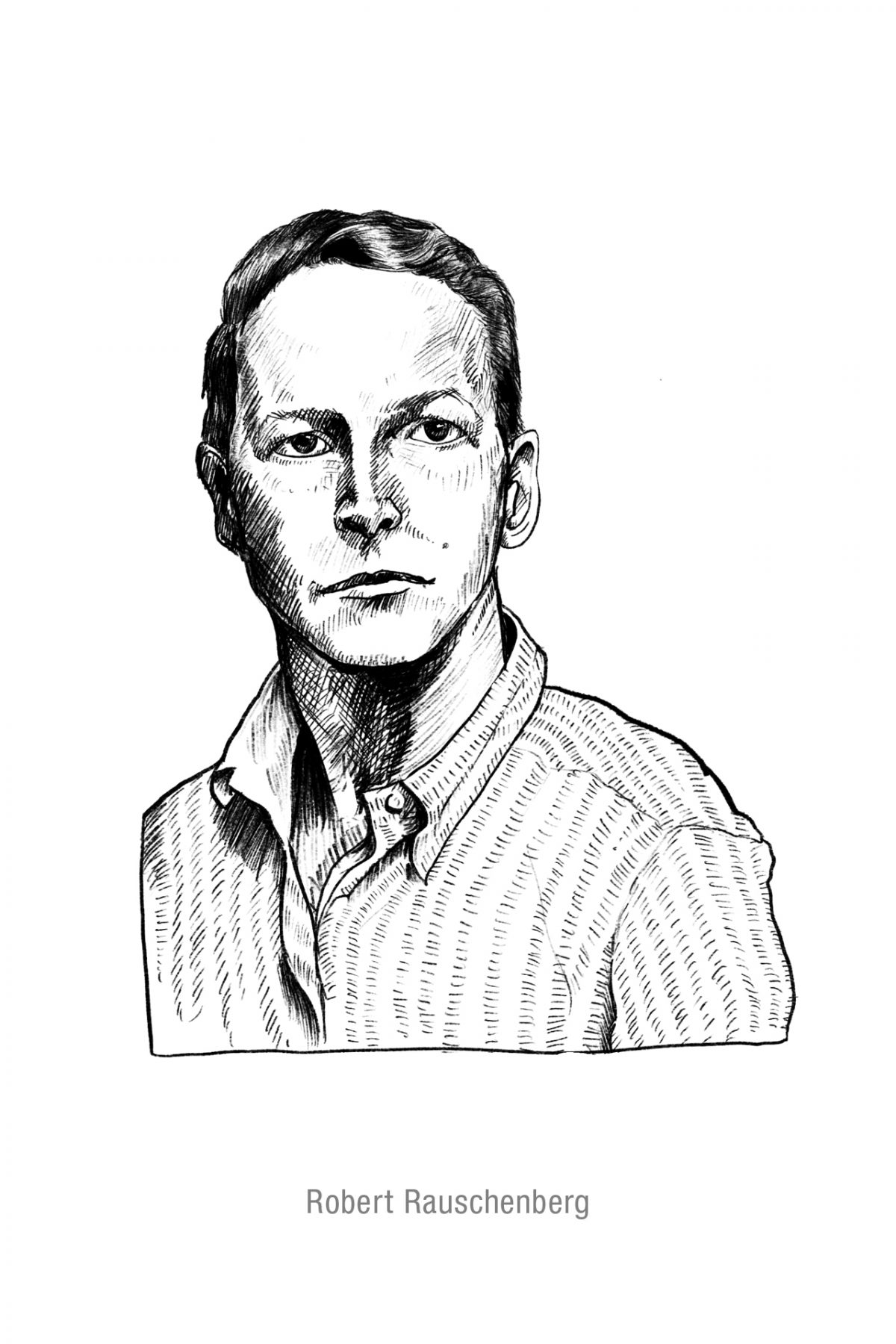

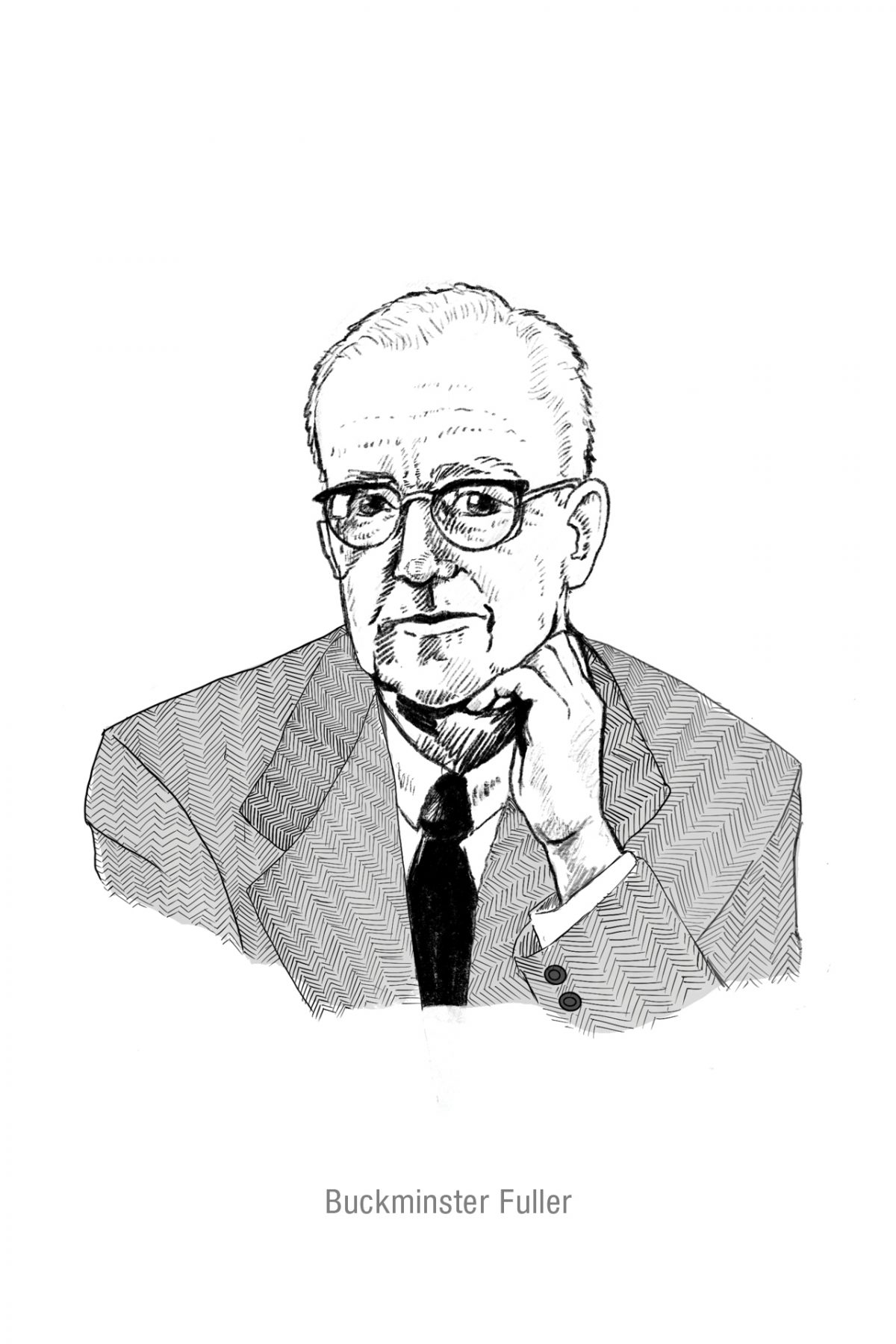

To break structural and hierarchical patterns dominant in traditional schooling institutions, BMC did not appoint any trustees or deans. However, the college was no stranger to noteworthy influence; throughout its run, the school’s advisory board included that of John Dewey, Walter Gropius, Carl Jung, Max Lerner, Wallace Locke, John Burchard, Kline, and Albert Einstein, among others. By the 1940s, word of the college and its open and inclusive community spread. This attracted more artists, many of whom emigrated away from the Nazi regime or were affected by the Second World War. Throughout its short life, the likes of both American and European creators such as Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, Jacob Lawrence, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, and many more called the school home.

Students and faculty at the co-ed institution mingled as peers, which circa 1933-1941 was located at the Blue Ridge Assembly buildings, south of Black Mountain Village. In 1941, the college moved to its own campus at Lake Eden. In 1944, the school instituted its famed Summer Music and Art Institutes, bolstering it as a year-round institution. The summer sessions brought in “an influx of new and temporary people,” bringing an inimitable and exciting energy to the campus.

Each individual at the commune-reminiscent school contributed to its self-functioning; both students and faculty participated in the school’s daily operation, from cooking, to cleaning, and even farming —to constructing new school infrastructure. Faculty and students frequently ate together and worked together. It was understood that work, art, design, and community were interwoven — one must not only possess knowledge but also the will to practice to create. The interdisciplinary experience of living and working both individually and collaboratively became part of the pedagogical influence of the school.

DEWEY’S INFLUENCE & THE TEACHING MODEL

The visionary idea of BMC, both novel in physicality and concept form, was heavily predicated on John Dewey’s Democracy and Education. Dewey, an early founder of American pragmatism, believed in individualism. The importance of individual will was embedded into the pedagogy of BMC (something that was unique to American ideology and under siege in much of Europe before and during the war). Students were encouraged to set their own curricula and course structures; exams and set timetables did not exist. Instead, the students and faculty cherished the spirit to have the space to experiment, work freely, and learn empirically.

At the base of most liberal arts curricula is the study of philosophy. Dewey denounced the idea that philosophy is a mere subject of education. He, instead, maintained that philosophy and education are one in the same. He believed that “philosophy had become an overly technical and intellectualistic discipline, divorced from assessing the social conditions and values dominating everyday life.” Following Dewey’s convictions, BMC, in retrospect, “sought to reconnect philosophy with the mission of education-for-living…”

“There was the joy of finding this freedom of living unbound by the conventions of society…the exquisite and delightful balance of the freedom of personal life or activity of the students, free to learn about themselves and their relationship to life, to each other, to anybody who came there.” — Sculptor and student at BMC, Richard Lippold

LASTING INFLUENCE

Although Black Mountain College was short-lived, its impact and influence have been lasting. Its progressive principles, where arts were given equal status to academia, live on in various institutions today. The informal teaching and outdoor activities have continued to guide the principles of education. The school’s pursuit of individualistic philosophy carried into the canon of art even after the college closed. As legendary in its own time as it is today, BMC fostered eminent souls — artists, intellectuals, poets, dancers, musicians, and more — whose work has inspired generations of successive artists and thinkers from around the world.