Body of Work — A Conversation with John Pawson13.04.2023

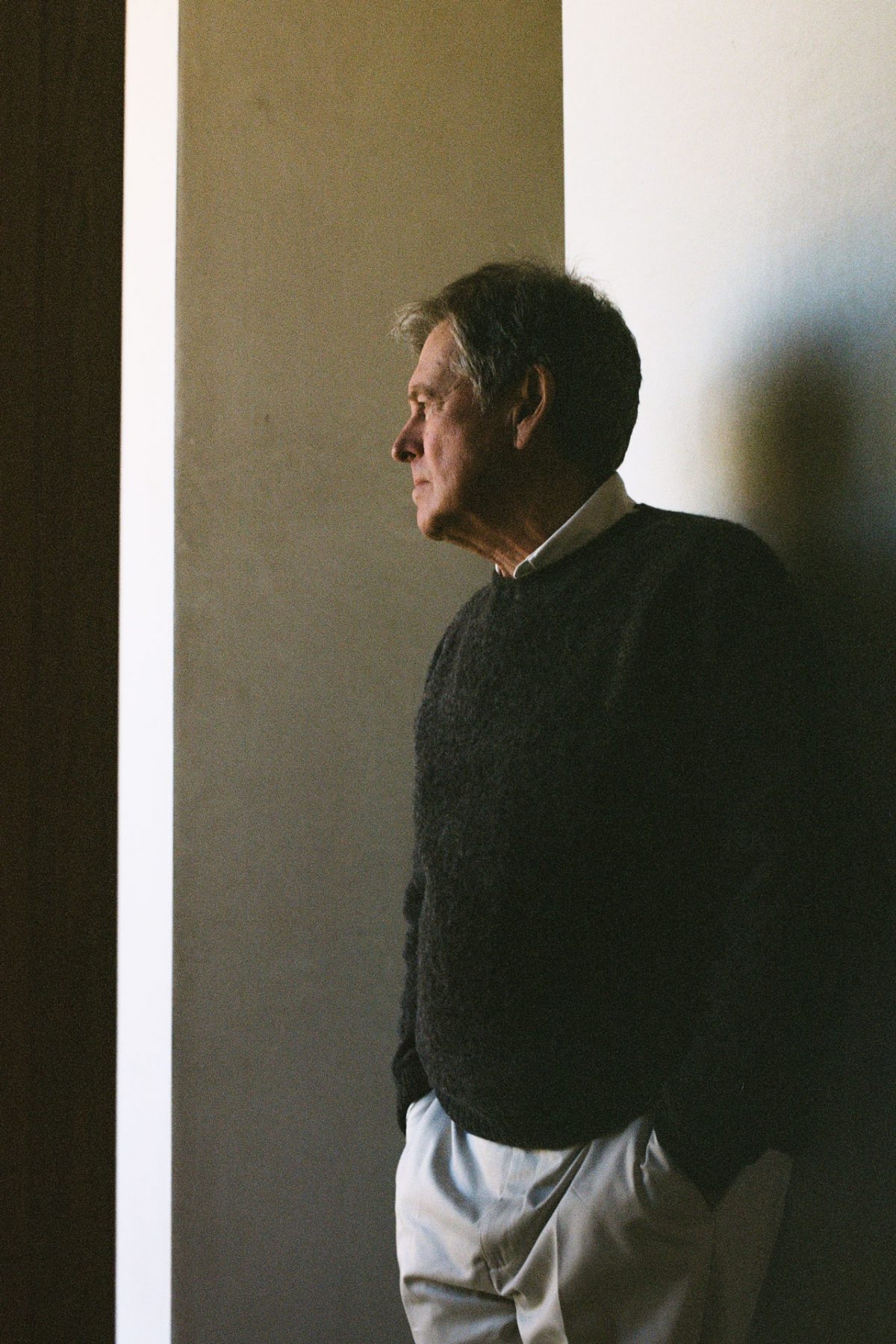

Somewhere in the rolling idylls of Oxfordshire, architect John Pawson busies himself in his library. His sprawling Home Farm is in character with the heritage farms of the area, but inside is littered with Pawson’s fingerprints. Its large windows pull in the late morning sun as it easily suffuses the space. Warming up the natural hues of stone, linen, and wood, the home grows with the light. Pawson’s home, dubbed Home Farm, has a reductive anima that underscores the sensual impression that is felt throughout every room. Simplicity isn’t the word for it — Home Farm is meticulous in its intention. Each beam, window, textile, and piece of furniture exists here for the sole purpose of conjuring comfort.

The light continues to fill each room, stopping to illuminate Pawson at his desk. Surrounded by books, he looks at ease as if he’s figured out how to balance work and life. We join Pawson here as he anticipates the release of a biography on his forty-year career. His cockapoo, Lochie, curled up on a woollen blanket, listens on as we begin.

First things first, tell us about your career’s origin story. Who were you before studying architecture?

I never did very well academically. I never got A levels. In fact, I did so badly in French and Spanish A level, that as a conciliatory, they gave me O levels at A level. So I’m a rare person that’s got two French O levels and two Spanish O levels [laughs].

I left school and went travelling for a couple of years. My father said, “If you don’t come back now, there’ll be no place in the family business for you.” He had some factories making women’s clothes. I spent six years working for dad near Newcastle, up in the northeast, and in Halifax in Yorkshire.

But, it didn’t really work out. I was going to get married, and that didn’t work out either. They both coincided at the same time, just before Christmas of 1973. Just then, I met somebody who sold me an around-the-world ticket. The first place I stopped was Tokyo, Japan. I had a friend in Nagoya, which is a couple of hours from Tokyo, and I went straight there. It was Christmas Eve, and following two failures in my life, it was a pretty low period. But, Japan cheered me up.

Tell us more about Japan. How did you become acquainted with Shiro Kuramata?

When things weren’t going too well for me, it coincided with me seeing a documentary on a Zen Buddhist monastery in the mountains in Japan. And I thought, “Gosh, that’s the answer. I’ll go away and forever become a Zen Buddhist monk.” I was 24 going on 12, I think. I had that schoolboy idea that I could suddenly transform myself into a Zen Buddhist monk.

My Japanese friend introduced me to his father, who was actually a Buddhist monk on the outskirts of Nagoya. He drove me up to Eihei-ji, and I tried one night there. I thought I was going for 10 years and ended up for one night. So I mean, that didn’t work, but I wanted to stay in Japan.

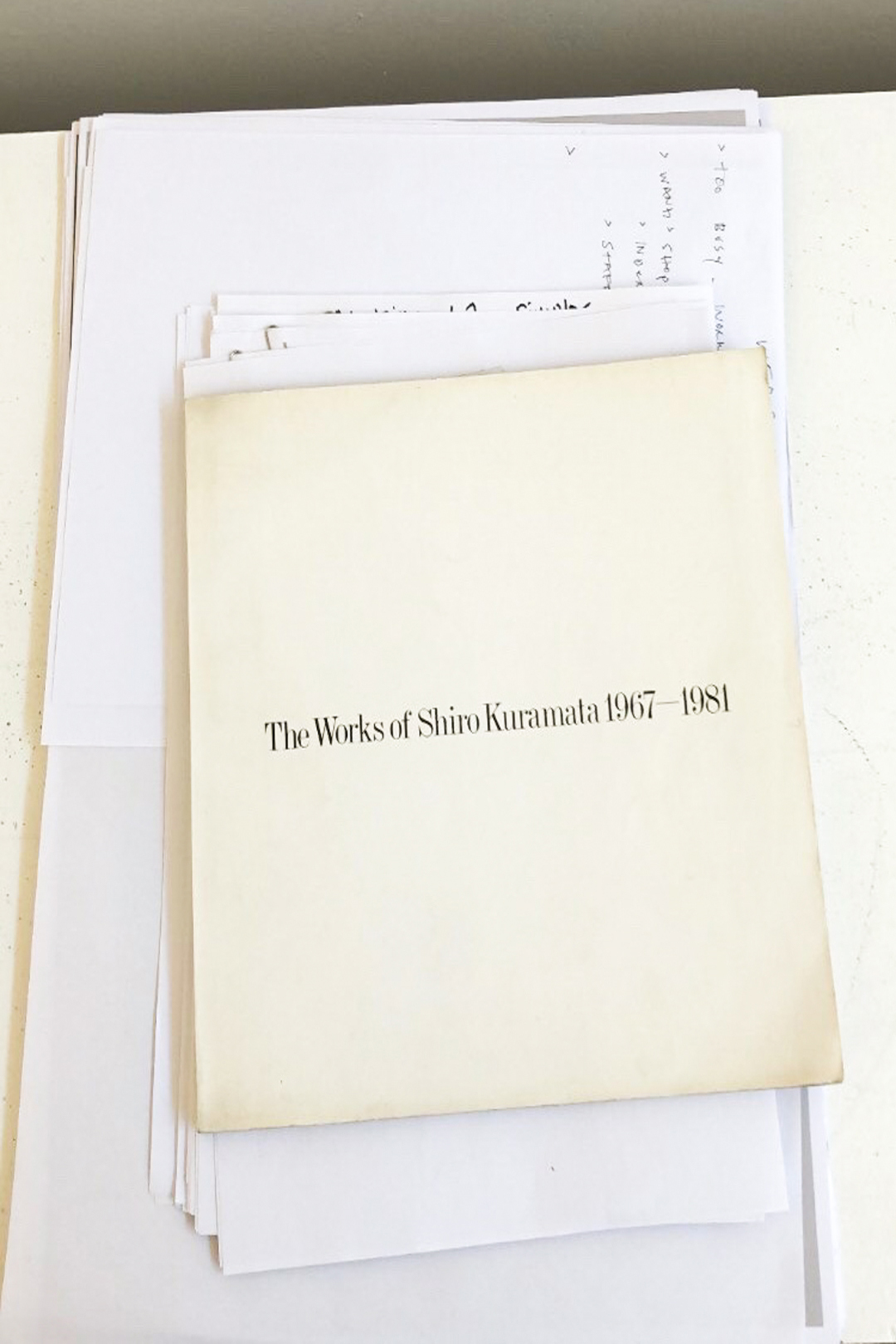

I’d seen a book in Tokyo on Kuramata and I thought, “This is the guy.” I called him and said, “I’m John Pawson, can we meet?” It was just the insouciance of a 24-year-old. Of course, I would never do it now, but you just don’t think of what you can’t do or what you shouldn’t do. I think he was just as mystified. He turned up, we had a coffee, and that was that

What else inspires your work?

Every movement in architecture gives you something. At school, you study different movements and you absorb things as you go. The most influential architect to me has been Mies van der Rohe. Somehow, he’s the ultimate architect. It wasn’t until I saw Kuramata’s work that I thought, “Well, here is a living version of Mies’s work.” I have a very sort of narrow personal taste, but Mies fulfils most of that.

What of your passions? Have they changed throughout your career?

I don’t think I’ve changed that much. Architecture has been the one thing that I came to relatively late to practice. It wasn’t until I was in my mid- to late-thirties that I actually started doing it. But, it had always been a passion for me, this idea of space and what made me feel different in space. But before that, there were lots of things that I was interested in besides architecture, like cycling.

“I don’t argue about being called minimal or minimalist, or whatever. But, in the work, I’m always trying to look for the essential. I’m more like an essentialist, I suppose. It’s about trying to find clarity in the work and refining it until it’s as good as it can get.”

You’ve been hailed as a minimalist, but how would you describe your design philosophy?

It’s funny how popular the word minimal has become. I don’t argue about being called minimal or minimalist, or whatever. But, in the work, I’m always trying to look for the essential. I’m more like an essentialist, I suppose. It’s about trying to find clarity in the work and refining it until it’s as good as it can get. Architecture’s difficult because you’re building which is an imprecise business; it’s very, very difficult to get it perfect. You can’t keep on working at it. You can’t move walls once they’re up. You can’t change space once it’s been created because, whereas with an object, you don’t have to put it into production until you think it’s sort of as good as you can get.

When I was working for the monks, I told them I wanted to make it perfect. They said, “Well, only God is perfect.” It’s funny that a client will settle on 99 per cent as being good enough.

“I wouldn’t necessarily say difficult, but you have the same drive to make each project as special as possible. Otherwise, there’s no point. Everything has to be done as intensely as possible, however small or big. Being human, not every project works out as successfully as another, but you approach each one exactly the same.”

Can you tell us about some of your more difficult projects and the important things you’ve learned from them?

I’ve been doing this for 40 years. Every project is … I wouldn’t necessarily say difficult, but you have the same drive to make each project as special as possible. Otherwise, there’s no point. Everything has to be done as intensely as possible, however small or big. Being human, not every project works out as successfully as another, but you approach each one exactly the same. You try and keep your head down, and then occasionally you raise it to review the work in a book or something, then move on.

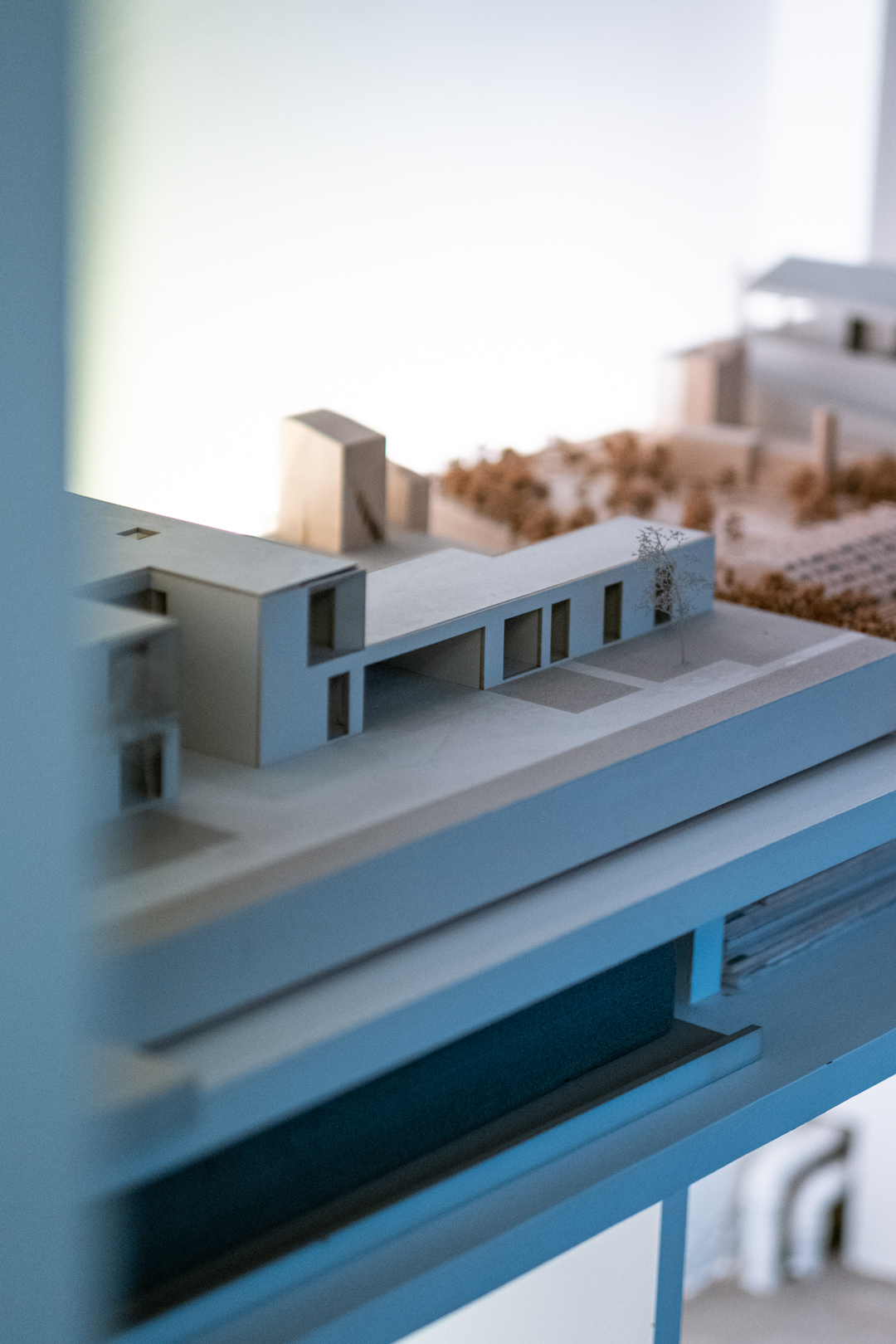

How do you approach architecture’s fundamental problems when you’re setting a new project in motion?

Designing is, I find, a very methodical business. You learn how to design, but the way I approach things is: you have a site, you visit the site, you take note of the local architecture, you take note of the climate, the flowers, the flora and fauna. At the same time, you are listening — usually to the client,

because they want you to be there when they see it. You have these two things you have to deal with. Luckily, the brain can cope. You’re wandering around in this strange state, taking it all in. Then, you go back and you have a blank piece of paper and you make a start. The big trick is not to hang around too long. I mean, you make a start, whatever it is, even if it’s wrong, or completely the opposite.

“Every project is approached with the same rigour. We also ask ourselves: is it necessary? Is it the most direct design we can produce?”

It’s easy to lose sight of the big picture. Is it possible to be pragmatic in design?

The way we — my team and I — handle it is with our own set of rules. They’re clearly set down at the beginning. Every project is approached with the same rigour. We also ask ourselves: is it necessary? Is it the most direct design we can produce?

There’s a huge amount of fun in the office, but there’s no humour in the work. There’s no room for jokes with architecture, in my opinion. I mean, you see plenty, but it’s a very serious business.

As a creative, it’s too easy to edit your work to death. How do you temper this urge? How do you know when a project is finished?

[Laughs] It is very difficult not to edit when it’s your personal house or your project. When I first started, I always said, “If I get a new house to design, then I’ll be able to prove that I can do it and I’ll be able to show this off.” For a long time, [the studio] only had one house, so we would overdo it. With the Mallorca house, we found the form for it rather quickly. After that, it was about trying other things to prove that the first one was right. When you’ve got a few jobs on at the same time, you can’t over-refine because you don’t have the time. You know when you’ve found the essence of it.

My point is that there must always be an idea, otherwise, it’s not architecture. There has to be an idea behind the design — a new idea: something special each time.

Your approach to materials is important to your work.

You don’t really realize the impact that a focus on the material has. If you are designing clothes, for example, material is everything. You start with one thing and then you design or cut it, or machine it, to shape how it is. My dad was an expert in that. He could tell the weight of something just by feeling it. He could probably tell you what it consists of, whether it was wool or silk or anything else. I picked that up.

But, I always felt designing clothes or making clothes was too transitory. I mean, the fact that you had to have a new collection every season, I found very stressful and not very calming. I’d always been interested in building. So, somehow, when I eventually got to the knowledge of materials, I think it helped.

“In architecture, stone and wood, and obviously glass and steel and plaster form the basis of everything. When I first started, I narrowed that down. It was straight grain Japanese oak, usually bleached, white Carrara marble, raw plaster, and white paint. That was about it.”

How do you select the materials you use? Is it for their purpose or their aesthetics?

Most of the materials that I use are natural. In architecture, stone and wood, and obviously glass and steel and plaster form the basis of everything. When I first started, I narrowed that down. It was straight grain Japanese oak, usually bleached, white Carrara marble, raw plaster, and white paint. That was about it. Then, of course, you do other projects and you suddenly realize that not everybody wants sand-coloured stone, some want grey.

You speak to the importance of natural light in your work. What is your relationship with the natural world?

There’s no architecture without natural light, which was, I think, what Louis Kahn said.

I really understand the specialness of cities. Living in the city is intellectual and in every way stimulating. I couldn’t exist without art, architecture, and everything else. It just wouldn’t be sustainable or fulfilling for me. But, you sometimes wonder what we’re doing on the planet by getting rid of nature. There’s something so wonderful about — if you’re privileged enough — going to deserts, especially something like the Karoo in South Africa. You can drive for hours and hours and not see anything. When you open the door to the car or stop the engine, the silence is extraordinary.

I do love the real wild and I do love the really intense city. I feel optimistic that we will find a way to not deplete what we’ve got, but it’s a scary balance at the moment.

“However direct or simple you can make the architecture, in the future, it could become dated, even though you’re trying to make it as simple and unfashionable. But, you are trying to make the architecture last. That’s the responsibility because you’re building with bricks and mortar. It’s not something that will disappear easily.”

What is the balance of function and fashion in your work?

As I said, my father’s business was making fashion and making clothes. My mother’s side was in top-making and spinning, making the fabrics and things like that. I’ve always liked architecture because it’s not transitory and it’s not fleeting. In a way, fashion, the very word seems to suggest change in my mind. I always found it difficult to be constantly designing new collections and coming up with new ideas every six months. Or now, of course, it’s every two months [laughs]. For me, it’s the permanence of architecture.

How does permanence relate to your design, especially in a world with such a violent need for replacement?

Fashion always comes into [my design]. However direct or simple you can make the architecture, in the future, it could become dated, even though you’re trying to make it as simple and unfashionable. But, you are trying to make the architecture last. That’s the responsibility because you’re building with bricks and mortar. It’s not something that will disappear easily. The idea of permanence is a good thing in one sense. Of course, if you build something, so you have to be sure that what you’re building is something that people will want to have around.

You journal quite often. Is it a process of introspection for you?

I find it very calming to be able to take photographs because I’m capturing a moment which I know will never be again. It relaxes me. But, of course, there are so many moments and you end up taking a huge amount of photographs, so I’m not sure how calming it really is in the end [laughs]. I was taking 50,000 or 100,000 a year or something like that. I mean, I have a database of half a million, I think. That’s the difference with digital, however. Before that, I used to take prints. There was a shop I used to go to call Snappy Snaps. I’ve got thousands of negatives of the same thing. It’s just … I think you frame it in your head when you see things and it’s just a natural outcome of that mental framing. You need to have a natural reproduction of that. I never thought I would do anything with the photographs. They connect to the architecture in the sense that it’s my eye. But, people are surprised that what I photograph doesn’t visually relate to the work. There’s a lot of colour, there’s a lot of pattern, but it’s not necessarily in the work.

“I’m actually, by nature, not that patient or not that painstaking. I mean, I love order, because my head is so messy.”

What do you get from photography that you don’t get from design?

Immediacy. I’m actually, by nature, not that patient or not that painstaking. I mean, I love order, because my head is so messy. But it’s the ability to take a photograph and control that. It’s a quick thing. In designing buildings, you can work on a project for five years or ten years even. Whereas a snap is literally that. A snap.

Tell us more about your upcoming exhibit in Tokyo.

We’ve been offered this exhibition at The Mass Gallery in Tokyo, which is three different pavilions in the centre behind Omotesando in Shibuya. It has these beautiful, modern concrete pavilions, one of which is outside. They’re showing works from my book, Spectrum. I’ve done a new series of photographs called Home, which is a self-portrait, really. They’re pictures of this house and from the house in London. They are a self-portrait, even though they’re photographs of interiors. They reflect me.

A new book on your life, Making Life Simpler, comes out this year.

Hooray! [laughs]

What was it like to work with your friend, Deyan Sudjic? Were you hoping for a flattering depiction of yourself or a brutally honest one?

Somewhere in between [laughs]. Deyan is a very astute guy and writes very eloquently. The advantage is that he’s been around for all the highs and lows of my career and private life, actually. He’s been around when Calvin Klein first came to call, he’s been around when I’ve lost jobs, and he’s introduced me to jobs. In a sense, he’s been as close as anybody to the work.

But, of course, he is an architectural critic. It is what you would call an “authorized biography”, so it’s not meant to be an exposé or anything. It’s just a story about how you put architecture together.

How does it feel to have such a culminant piece come together at this point in your life?

You tend to assume that a biography is done at the end. Let’s hope this is a halfway house [laughs]. I’ll be living till 140.

What more do you want to achieve in your career?

Well, it’s funny because I never set out to be an architect. I never thought I would have an office or a studio. Nothing was mapped out. I tend to just follow the river. What happens next? I’m not really sure. I mean, I didn’t want a 70th birthday because I didn’t want to be 70. It just seemed too much of a milestone and conjured up too many things. I was going to be 69 for a long time, but Catherine, my wife, scotched that. She said, “You’ve got to have a party.” I’m glad I did, but it still reminds you — not daily, but often — to get to grips with what the next 10 years will be. Oscar Niemeyer was 103, but his wife was 60; not sure if that’s got anything to do with it [laughs].